Legal and Judicial History |

A trial in Richfield, Territory of Utah. Frontier justice was often rough and arbitrary by modern standards. Courtesy Nelson Wadsworth.

by Robert E. Riggs

THE CHURCH of JESUS CHRIST of Latter-day Saints has usually relied upon the law for protection and has honored its judgments in principle and practice. The one significant exception was its resistance to antipolygamy laws before plural marriage was discontinued in 1890. Obedience to the law of the land is a tenet of LDS belief (see Politics: Political Teachings).

Despite this respect for law, nineteenth-century LDS history includes numerous encounters with the law. Peculiarities of doctrine and practice, accompanied by social cohesion that appeared threatening to outsiders, spawned both persecution and frequent litigation for the Church and its leaders. In western New York, where the Church had its genesis, and in Ohio, where the Prophet Joseph Smith moved in 1831, evenhanded justice was generally available in the courts. Three times in New York, Joseph Smith was tried and acquitted for "vagrancy" and "disorderly conduct," the charges stemming largely from religious hostility (see Legal Trials of Joseph Smith). In Ohio the Prophet and other Church leaders used the courts affirmatively to obtain redress against religious persecution. Near the close of the Ohio period, the failure of the Kirtland Safety Society (see Kirtland Economy), a lending institution, brought a host of lawsuits against individual Church leaders who had sponsored it. The society was engaged in banking activities without a legal charter and collapsed in the wake of bank failures that swept the nation in 1837. Numerous judgments were obtained against Joseph Smith and other principals, some of which they were unable to pay, but anti-Mormon bias appears not to have been a factor in the decisions.

In Missouri, where the Latter-day Saints began to gather in 1831 and where the Prophet went after fleeing Kirtland in January 1838, the courts were less sympathetic. In 1833-1834 the Saints were forcibly expelled from Jackson County and forced into Clay County, Missouri, by mob violence. After resettling in nearby Caldwell and other Missouri counties, they were again driven from their homes in 1838-1839 by armed mobs abetted by the state militia. In neither instance were they able to obtain judicial redress for loss of life and property. Instead, incident to the expulsion from Caldwell County, Joseph Smith and other Church leaders were arrested as instigators of the violence on charges of larceny, arson, and murder. Most of the prisoners, including the Prophet, were later allowed to escape, and they fled to Illinois. Two who reached trial were acquitted for lack of evidence.

In Illinois, for a time, the Saints had a more favorable experience with the law. Courted by Illinois politicians, they obtained a liberal state charter for their city of Nauvoo. Under the Nauvoo charter the local court consisted of the mayor of Nauvoo and the city aldermen, who were also Church leaders. By ordinance, no legal process issued in any other jurisdiction could be served in Nauvoo except by the city marshal, and then only when countersigned by the mayor. The Nauvoo court made extensive use of the writ of habeas corpus to free persons held under arrest warrants issued by courts outside Nauvoo. Joseph Smith was discharged from arrest several times on writs issued by the Nauvoo court; he also obtained habeas relief from the federal district court in Springfield, Illinois. In June 1844 the Prophet accepted the need to stand trial at Carthage, the county seat, on charges arising from the Nauvoo city council's decision to declare the Nauvoo Expositor (a newly created opposition newspaper) a nuisance and destroy its printing press. While imprisoned in Carthage Jail awaiting trial, he and his brother Hyrum were killed by a mob. (See Martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum Smith) His accused assassins were tried and acquitted. The Illinois legislature repealed the Nauvoo Charter in January 1845, and in early 1846, threatened by mob violence, the Saints began a westward exodus that ultimately led to Utah.

In Utah, local government officials were usually Church leaders, and the territorial legislature and local judges were drawn almost exclusively from Church membership. When the Utah Territory was formally organized in 1850, Brigham Young, President of the Church, was appointed territorial governor. A system of ecclesiastical courts was established alongside the territorial courts, and most disputes between Church members were settled there rather than in the civil courts. Except in special circumstances, suing a brother or sister in a civil court constituted "un-Christianlike conduct," for which a penalty of Church disfellowshipment was often imposed. Nonmembers occasionally took their civil claims to Church courts as well. The county probate judge was usually a local Church leader, and probate courts were important in the judicial system because the territorial legislature had given them broad jurisdiction in both criminal and civil matters. Congress abolished the general jurisdiction of the probate courts in 1874 as part of the federal campaign against polygamy.

Tension between the Church and the federal government in Utah appeared almost from the beginning. Several federal appointees to the territorial government in 1851, including two of three federal judges, clashed with Church officials and the territorial legislature and quickly left the territory. Their negative reports to the President of the United States and to the public helped lay the foundation for future misunderstanding. The tension reached crisis proportions in 1857 when U.S. President James Buchanan, acting on false reports of a Mormon rebellion, sent an army of 2,500 men to ensure the authority of a new territorial governor, Alfred Cumming of Georgia (see Utah Expedition). The confrontation was resolved without bloodshed, but it signaled a conflict not to be mitigated until after 1890, when the Church officially discontinued the practice of plural marriage and adopted a less intrusive role in the political and economic life of Utah.

Courts and the law, rather than military force, became the means of enforcing Church capitulation to the mandates of the larger secular society. The U.S. Supreme Court, in Reynolds v. United States (98 U.S. 145 [1879]), ruled that the First Amendment right to free exercise of religion did not exempt Mormon polygamists from prosecution under the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act (1862), and this paved the way for even harsher anti-Mormon legislation (see Antipolygamy Legislation). Unlawful cohabitation, easier to prove than a bigamous marriage, was made a crime in 1882. Other legislation found constitutional by the courts had the effect of excluding Latter-day Saints from territorial juries, denying them the right to vote or hold public office, denying polygamists' children the right of inheritance, and hindering the immigration of Church members from abroad. Church leaders were repeatedly harassed by vexatious lawsuits. Pressure on the Church climaxed when the U.S. Supreme Court, in The Late Corporation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints v. United States (136 U.S. 1 [1890]), upheld provisions of the 1887 Edmunds-Tucker Act that disincorporated the Church and authorized confiscation of most of its property. On September 24, 1890, President Wilford Woodruff, by revelation, issued the manifesto discontinuing the practice of plural marriage. Although a number of property issues remained, the Manifesto spelled the end of the nineteenth-century legal confrontation between the Church and the U.S. government.

In the twentieth century, the Church has avoided conduct that might bring it into conflict with the law of the land. Since the official discontinuance of plural marriage, no Church-sanctioned practices have posed a direct challenge to current legal norms. Disputes over property, business matters, and personal-injury claims have occasionally led to lawsuits, and legal claims sometimes have arisen out of specialized Church operations, such as LDS Social Services and Brigham Young University. Church activities outside the United States have also produced occasional lawsuits as the Church has expanded internationally. For the most part, this litigation has had little significance for the central mission of the Church or for issues of religious freedom. Compared with other large institutions in modern society, the Church has not been litigious.

A few court actions affecting the Church have had special significance, however. The decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Corporation of the Presiding Bishop of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints et al. v. Amos et al. (483 U.S. 327 [1987]) was a notable affirmation of religious group rights under the U.S. Constitution. The suit was brought by former employees of the Church-owned Deseret Gymnasium, Beehive Clothing Mills, and Deseret Industries who were discharged for failing to meet religious qualifications for participation in LDS temple worship. The employees alleged religious discrimination in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In defense, the Church invoked section 702 of the act, which expressly exempts religious organizations from the statutory prohibition of religious discrimination in employment. The lower court found that the section 702 exemption violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment, a constitutional bar to laws having the purpose or primary effect of advancing religion. The Supreme Court unanimously disagreed, holding the statutory exemption to be a permissible governmental accommodation of religion, at least as to nonprofit activities. The Amos decision is an important statement of the right of religious organizations to preserve their institutional integrity by maintaining religious qualifications for employees.

In two other establishment clause cases, Church practices were implicated, although the Church was not a party. Lanner v. Wimmer (662 F.2d 1349 [10th Cir. 1981]) was a challenge to the Logan, Utah, school district policy of granting released time and high school credit for students attending weekday LDS seminary classes. The court decided that released time was permissible governmental accommodation of religion but that granting of credit was not. The second case, Foremaster v. City of St. George (882 F.2d 1485 [10th Cir. 1989]), involved a citizen's objection to the city's subsidization of exterior lighting of the LDS St. George Temple and to the use of a replica of the temple on the St. George city logo. Although St. George claimed it was using the temple to enhance the city's image, the federal appeals court ruled that the city was thereby endorsing the Church in violation of the constitutional rule against establishment of religion.

The Church and its members have helped to define the statutory rights of religious groups through litigation of tax exemption laws in a number of U.S. and foreign jurisdictions. In England the Church's claim to a statutory property tax exemption for its London Temple was ultimately decided by the House of Lords, the highest court of appeal (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints v. Henning, 2 All E.R. 733 [1963]). The Lords denied the exemption because the temple, with its restrictive admission requirements, did not qualify under the statute as a place of "public worship." Henning has been frequently cited in British cases interpreting the property tax exemption statute. It was cited but not followed in the New Zealand Supreme Court decision of Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Trust Board v. Waipa County Council (2 N.Z.L.R. 710 [1980]), in which the court, interpreting a New Zealand statute, granted a property tax exemption to the LDS temple in New Zealand. Property tax exemptions for Church property have also been litigated in a number of U.S. states, most commonly in relation to Church Welfare farms. Exemption for such property has been denied by courts in Arizona, Idaho, and Oregon, but upheld in South Carolina. In each case, the outcome has turned on the wording of the statute defining the tax exemption.

Of some practical importance for Church members in the United States was the 1990 decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Davis v. United States (110 S.Ct. 2014 [U.S. 1990]). In an income-tax refund suit brought by parents of two former missionaries, the Court held that funds sent directly to missionaries for their support were not deductible as a charitable contribution. To qualify as a charitable deduction, the funds had to be given to the Church itself or else donated through a trust or other legally enforceable arrangement, for the benefit of the Church.

Occasionally other legal actions have been of interest to the Church, even though the Church was not a party and no Church activities were directly at issue. One highly publicized case was the prosecution of Mark Hofmann for two 1985 Utah murder-bombings and various document forgeries. The Church was interested because many of the Hofmann forgeries purported to shed new light on the early History of the Church and had been widely accepted as authentic. After a preliminary hearing, the prosecutors accepted a plea bargain mandating life imprisonment. Another widely noted case indirectly affecting the Church arose from an Idaho court challenge to the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). The Church had taken a strong official stand against the ERA, and proponents of the amendment claimed that U.S. District Judge Marion J. Callister would be biased on the issue because he was a prominent local Church leader. Judge Callister refused to disqualify himself (Idaho v. Freeman, 478 F. Supp. 33 [1979], 507 F. Supp 706 [1981]) and subsequently ruled against the ERA on the major issues. On appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, the case was dismissed as moot because the time for ratification of the ERA had expired (National Organization for Women, Inc., et al. v. Idaho et al., 459 U.S. 809 [1982]).

(See Daily Living home page; Church History home page)

Illustrations

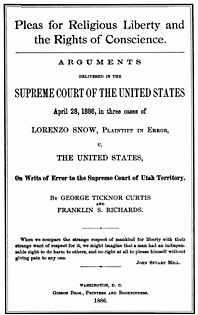

Two appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court by Lorenzo Snow regarding "cohabitation" were dismissed on jurisdictional or procedural, grounds. However, Snow's arguments, published in this 1886 document, maintained that his case turned, not on procedure, but on basic religious freedoms and rights of conscience, as had the earlier case of Reynolds v. United States. Courtesy John W. Welch.

Bibliography

Allen, James B., and Glen M. Leonard. The Story of the Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, 1976.

Burman, Jennifer Mary. "Corporation of Presiding Bishop v. Amos: The Supreme Court and Religious Discrimination by Religious Educational Institutions." Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics and Public Policy 3 (1988):629-62.

Driggs, Kenneth David. "The Mormon Church-State Confrontation in Nineteenth-Century America." Journal of Church and State 30 (1988):273-89.

Firmage, Edwin Brown, and Richard Collin Mangrum. Zion in the Courts: A Legal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830-1900. Urbana, Ill., 1988.

Encyclopedia of Mormonism, Vol. 2, Legal and Judicial History

Copyright © 1992 by Macmillan Publishing Company

All About Mormons |