Church History c. 1898-1945, Transitions: Early-Twentieth-Century Period |

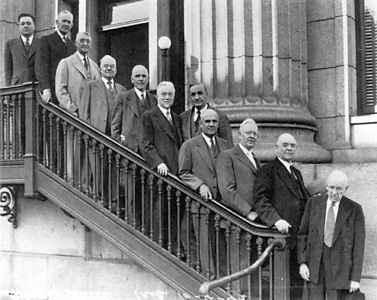

The First Presidency (1934-1945) on the steps of the Church Administration Building (c. 1942). President Heber J. Grant (center), first counselor J. Reuben Clark, Jr. (left), second counselor David O. McKay (right). Courtesy Edward L. Kimball.

by Ronald W. Walker and Richard W. Sadler

Overview: "At the turn of the century the Church's finances suffered from the lingering effects of the federal crusade against Polygamy and the public doubted that its recently declared cessation of Plural Marriage had indeed taken effect. After discussing developments in these two areas, this article looks at the Latter-day Saints' integration into the larger American society, including examining the Church's position on war and peace. It also reviews the efforts to systematize that accompanied the steady growth throughout this period." Encyclopedia of Mormonism

The Church entered the twentieth century beleaguered and isolated. The LDS experience hitherto had involved founding, exodus to the isolated American West, building there a spiritual and temporal kingdom of God, and grappling with an unsympathetic and often hostile larger American community. The year 1898, however, was a watershed. Following the death of President Wilford Woodruff in September, Lorenzo Snow (1898-1901) succeeded to office and began a series of changes aimed at renewal and redefinition. He, along with his successors President Joseph F. Smith (1901-1918) and President Heber J. Grant (1918-1945), reacted to the sweeping changes of the first half of the twentieth century and reached back to preserve old values in a rapidly changing world. The result by the middle of the century was a Church accepted by and integrated into American society, more vigorous and vital than anyone but its most stalwart defenders might have foreseen a half century earlier.

An immediate problem was finances. The antipolygamy crusade (see Antipolygamy Legislation) had severely impaired revenue and assets, first by incarcerating leaders who normally managed donations and second by seizing and mismanaging Church property. The Panic of 1893 and the resulting depression made the situation worse. In an effort to provide employment and stimulate the local economy, leaders had borrowed money to fund public works and business projects. President Snow quickly ended this practice. His administration slashed expenditures, sold nonessential property, and urged followers to increase their financial contributions.

He dramatically announced this new policy in a southern Utah preaching tour. In May 1899, speaking to assembled members in St. George, he promised that faithful compliance to the Church's longstanding tithing code would bless members and at the same time free the Church from its debts. A year after President Snow's tithing emphasis, Church income doubled. Leaders also encouraged cash donations instead of in-kind commodities and instituted systematic spending and auditing procedures. Because of these reforms, by 1907 President Smith was able to announce that the Church at last had retired its debt. Annual tithing receipts stood at $1.8 million, in contrast to the Church's 1898 debt of $1.25 million. Moreover, the Church had property worth more than $10 million. The Church never again resorted to deficit spending, not even during the Great Depression.

President Snow's reforms did not preclude the holding of investment property or controlling of businesses by Church officers and directors (see Economic History). While some enterprises were divested, such as the Deseret Telegraph, the Utah Light and Railway Company, and the Saltair Resort at the Great Salt Lake, the Church particularly invested in concerns that advanced its social or institutional purposes. It retained the Deseret news, and in the early 1920s leaders established one of the country's first radio stations, later known as ksl radio. The Salt Lake theatre, the pioneer playhouse, was returned to the Church to provide sanctioned recreation—only to close at the onset of the Depression because of reduced box office revenues and what Church leaders thought were declining theatrical values.

Drawing on the precedent of the Nauvoo house, Salt Lake City's Hotel Utah was built to draw tourists from hostile non-Mormon hoteliers and enhance the Church's image. The Beneficial Life Insurance Company provided low-cost insurance. The Utah Sugar Company, transformed into the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company, continued to provide local farmers a market for their most important cash crop, while Zion's Cooperative Mercantile Institution (ZCMI) and Zion's Savings Bank & Trust attended the public with competitive retailing and banking services. This altruistic investment policy was also pursued on a broader level. Church leaders sat on the board of other corporations important to the region.

These investments and the social concerns they expressed harked back to the pioneer ideals of community concern and uplift. They were not the only remnant of the past. Plural marriage continued to be a troublesome issue for Latter-day Saints and focused national attention on the Church, particularly during the Snow and Smith administrations. Although many members believed that the 1890 manifesto ended plural marriage, others interpreted the pronouncement as simply shifting the responsibility for practicing it from the Church to the individual. As a result, from 1890 to 1904 some plural marriages continued, though on a greatly reduced level. Moreover, while some husbands stopped living with plural wives, most felt a moral and spiritual obligation to continue caring for their families.

This confusion and ambiguity spilled over visibly into politics. In 1898 Elder B. H. Roberts, a member of the first council of seventy and the husband of three wives, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. The Salt Lake Ministerial Association and similar organizations elsewhere used Roberts's election to focus on continuing plural marriages, charging the Church with failure to abide by the agreements that had brought Utah statehood. Anti-Roberts petitions containing seven million signatures flooded Congress and the House eventually refused Roberts his seat.

Still more serious was the case of Reed Smoot. The 1903 election of Smoot, a monogamous member of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, to the U.S. Senate once more stirred national uproar. The Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections commenced hearings on Smoot in 1904 (see Smoot Hearings), but Congress focused more often on the Church itself. Were church and state truly separate in Utah? Did the Church control the conduct of its members? Did it encourage polygamy and polygamous cohabitation? During the two-year investigation, President Joseph F. Smith and other leaders testified before the committee. Others, such as Matthias F. Cowley and John W. Taylor, suspected of performing plural marriages since the Manifesto, refused. To close the controversy and demonstrate the Church's willingness to make the question a matter of discipline, President Smith announced a "Second Manifesto" that expressly forbade future plural marriages. He also required the resignations of both Cowley and Taylor from the Council of the Twelve. In 1907 the Senate narrowly voted to allow Smoot to retain his seat.

Plural marriage still failed to recede entirely, even in the face of the now resolute policy of President Smith and later President Grant. Elders Cowley and Taylor, for instance, each received further discipline for additional plural marriage activity, the former being "disfellowshipped," while Taylor, after taking an additional plural wife, was excommunicated. Their conduct was similar to that of a growing number of former Mormons in the twentieth century. Styled fundamentalists, they accepted automatic excommunication rather than yield on plural marriage or discard other nineteenth-century practices. Unlike Latter-day Saints generally, who were strengthened by their belief in current prophetic revelation and therefore approached new times in new ways, the Fundamentalists faced the modern world by looking backward.

Nor did the plural marriage issue go away in the popular press. During the first decade of the twentieth century and even beyond, the Church came under severe public scrutiny by muckrakers and political opponents in Utah. Newspapers, magazines, and cinema in both the United States and Europe focused on sensationalized (and often fictionalized) aspects of polygamy, depicted Church leaders as autocrats, and denounced the Church as un-American and un-Christian (see Anti-Mormon Publications; Stereotyping of Mormons). Old charges of danite atrocities and blood Atonement resurfaced. In Utah the assault was led by two former U.S. Senators, Frank J. Cannon and Thomas Kearns, who used the Salt Lake Tribune to launch bitter attacks on Smoot and the Church and to support the American Party. This short-lived, anti-Mormon political party controlled Salt Lake City government from 1905 to 1911.

The Church attempted to meet the barrage of abuse even though the tide flowed strongly against it. Early efforts included promoting Saltair Resort and Salt Lake City's Temple Square as visitors centers. With the tabernacle organ and Mormon Tabernacle Choir as attractions, the latter site by 1905 annually drew 200,000 visitors. Attendance climbed steeply thereafter. When possible, leaders placed refutations in the muckraker publications. Moreover, a point-by-point rebuttal was read during the Church 1911 general conference. Perhaps the ablest and most enduring rejoinder came from B. H. Roberts. From 1909 to 1915, he issued a series of articles on Mormon history in the magazine Americana. These were later updated as Roberts's fair-minded, six-volume comprehensive History of the Church.

Increasingly men and women outside the Church also defended the Latter-day Saints. By 1900 C. C. Goodwin, a former editor of the anti-Mormon Salt Lake Tribune and longstanding critic, frankly labeled Mormons as successful, prosperous, and generally likable. Leading sociologist Richard T. Ely praised LDS group life. Morris R. Werner produced a Brigham Young biography devoid of previous stereotypes and hostility. These path-breaking ventures were followed by others. By the late 1920s President Grant conceded that virtually anything the Church might request could be placed in the media. Indeed Time Magazine gave President Grant cover treatment, while Hollywood studios completed such favorable motion pictures as Union Pacific and Brigham Young.

In part the change in public attitude came from the integration of Church members into the larger American society. Nineteenth-century Latter-day Saints expanded their agricultural settlements throughout the mountain West and even into Canada and Mexico (see Colonization), although their agrarian communities were often tightly knit, provincial enclaves. In contrast, as LDS outmigration continued in the twentieth century, Church members now rubbed shoulders with fellow Americans in urban settings. During the 1920s, for instance, the percentage of Latter-day Saints living in the intermountain West declined while those living on the American West Coast rose. In 1923 the Los Angeles Stake, the first modern stake outside the traditional Mormon cultural area, was created. Between 1919 and 1927 the number of Latter-day Saints in California increased from fewer than 2,000 to more than 20,000. The twentieth-century Church dispersion had begun, first with the migration of large numbers to the West Coast, then also with increasing volume to the East and Midwest.

Direct contact with neighbors lessened cultural, religious, and even emotional barriers, bringing Mormons and non-Mormons an increased appreciation for each other. The growing number of successful Americans who were also Latter-day Saints or Utah-born accelerated the process. Maud Adams was lionized for her widely popular stage portrayal of Peter Pan. Philo T. Farnsworth's inventions brought about television. Cyrus Dallin and Mahonri Young achieved distinction in the arts.

Latter-day Saints were particularly drawn to public affairs. Edgar B. Brossard became a member and then chairman of the United States Tariff Commission. J. Reuben Clark, Jr., rose in the higher levels of the State Department bureaucracy, finishing his government career as ambassador to Mexico. During the New Deal, Marriner S. Eccles was chairman of the Federal Reserve System. James H. Moyle served as assistant secretary of the treasury from 1917 to 1921, while William Spry was commissioner of public lands from 1921 to 1929. Heber M. Wells was the treasurer of the U.S. Shipping Board. Richard W. Young became a U.S. commissioner of the Philippines and returned from the First World War as Utah's first regular army general. For members of a once persecuted religious minority, each such personal success betokened the Church's growing acceptance and prestige. "Outsiders" were becoming "insiders."

Two Church members had disproportionate influence in shaping the Church's new image. One was Reed Smoot. Aloof, but honest and utterly tireless in his devotion to government duty and Church interests, Smoot remained in the Senate for thirty years. As chairman of the powerful Senate Finance Committee, he wielded major influence over American economic policy. More than any other Latter-day Saint in public service, he personified the Church, assuaging questions about its patriotism and integrity by his personality and presence.

The other was President Heber J. Grant. A businessman by inclination and early profession, President Grant's homespun ways and business-mindedness charmed an age given to commercial enterprise. Non-Mormons delighted particularly in his speeches. Concluding an address before the San Francisco Commonwealth Club, he was greeted with cries of "Go on! Go on!" When he addressed the Second Dearborn Conference of Agriculture, Industry, and Science, the "Chemurgicians" twice gave him standing ovations. His public relations ministry included more than delivering speeches. He promoted tours of the Tabernacle Choir. He personally guided nationally prominent business and political leaders through Salt Lake City and cultivated their friendship. He visited U.S. Presidents Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, and Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House. While President Grant was respected by his own people, non-Mormons also liked and idealized him.

The Church's sturdy growth during the period reflected its more positive image. Membership more than tripled during the half century; from the years 1900 to 1945 totals grew from 268,331 to 979,454. Prior to 1898 the Church had organized 37 stakes (16 were discontinued); by 1945 another 116 had been added. The Church's missionary force changed and increased accordingly, growing younger, attracting more unmarried individuals, and after 1898, including an increasing number of young women. At the turn of the century, fewer than 900 missionaries were called annually; by 1940 there were 2,117.

Missionary work continued to be a major preoccupation. The most ambitious new mission was Japan, opened in 1901 by missionaries led by Elder Heber J. Grant, then an apostle. Three years later the Mexican mission was reopened. The 1920s saw more than 11,000 German-speaking converts, though most converts came from English-speaking areas: Great Britain, Canada, and the United States, with the Southern States Mission being the most successful. Unfortunately, there as elsewhere, missionaries were subject to acts of physical violence. At the beginning of the century, annual convert baptisms were 3,786; a half century later the total had reached 7,877.

The Church sought to make its proselytizing more effective. Instead of dispatching missionaries without "purse and scrip," most now were financially supported by their families or local congregations. Missionary training classes were organized at Church academies and colleges. In the mid-1920s a Salt Lake City "Mission Home" for departing sisters and elders was inaugurated, where missionaries typically received lessons on proper diet, hygiene, etiquette, and especially missionary techniques and Church doctrine for two weeks. The era also produced new proselytizing tracts. Charles W. Penrose wrote a series entitled Rays of Living Light, James Talmage completed the Great Apostasy, and Ben E. Rich authored A Friendly Discussion. To preserve a sense of its heritage and to help tell its story, the Church purchased sites of significance to its early history (see Historical Sites): the Carthage Jail in Illinois (1903), where Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum had been killed; a part of the Independence, Missouri, temple site (1904); Joseph Smith's birthplace in Sharon, Vermont (1905-1907); and the Smith homestead in Manchester, New York (1907). At each of these locations, the Church eventually constructed visitors centers.

Perhaps more than by expansion, the era was characterized by internal consolidation. Lorenzo Snow's succession to office was symptomatic. For the first time the accession of the senior-tenured apostle to the office of Church president was completed within days instead of the past interregnums of about three years (see Succession in the Presidency). Recognizing the Church's increasing complexity, President Snow urged General Authorities to devote their full time to their ministry. By 1941 the question no longer was simply leadership efficiency but expansion. "The rapid growth of the Church in recent times, the constantly increasing establishment of new Wards and Stakes…[and] the steadily pressing necessity for increasing our missions in numbers and efficiency," the First Presidency noted in 1941, "have built up an apostolic service of the greatest magnitude" (CR [Apr. 1941]:94-95). In response to these new requirements, five men were appointed assistants to the Twelve. In contrast to the short-term laity that continued to occupy most Church positions, "general" Church officers—about thirty in number—now received compensation and served full-time, lifelong ministries.

Priesthood governance was also altered. The first half of the century saw a steady decentralizing of decision making as stake and local leaders received enlarged authority. The Church reduced the size of stakes to make them more functional and placed new emphasis on "ward teaching" (see Home Teaching). With smaller districts and more boys and men assigned to teaching, the percentage of families receiving monthly visits grew from 20 percent in 1911 to 70 percent a decade later. Finally, in a major departure from pioneer practice, members were urged to take secular disputes to civil and criminal courts rather than to Church tribunals. Once a means of regulating social and economic issues, Church courts now concerned themselves exclusively with Church discipline.

Priesthood quorums were strengthened. Priesthood meetings were now held weekly, with meeting quality improved by centrally generated lesson materials. President Joseph F. Smith in 1906 outlined a program of progressive priesthood advancement for male youth. Contingent on worthiness, young men received ordination to the office of deacon at the age of twelve, teacher at fifteen, and priest three years later. In turn, worthy men typically received the offices of elder and high priest, altering the nineteenth century dominance of the seventy among adult men. In 1910 quorums of high priest and seventy were realigned to coincide with stake boundaries, allowing closer direction by local authorities.

The tendency toward consolidation was also manifest in the Church's auxiliary organizations. Youth programs, once informal, diverse, and locally administered, increasingly yielded to centrally directed age group programs and unified curricula. The children's primary Association no longer served older youth, while the Young Men's Mutual Improvement Association (YMMIA) and its young women counterpart (YWMIA) included adolescents as young as twelve (see Young Men; Young Women). At first both the national Boy Scout and Campfire Girl programs were used for younger MIA members (see Scouting), but soon the latter was dropped in favor of an indigenous program. Activity programs received increasingly strong emphasis. With Sunday school and now priesthood quorums providing doctrinal instruction, the MIA increasingly turned to dance, drama, music, and sports. Church headquarters produced a magazine for each auxiliary: The Primary had the children's friend (1902) and the Sunday School the juvenile instructor (1900), later known as the instructor (1929). YMMIA had the improvement era (1897), YWMIA the young woman's journal (1889); in 1929 the two joined forces and the improvement era became the publication for both. Articles, curricula, and programs were periodically reviewed and correlated. For instance, a general Church Correlation Committee and the Social Advisory Committee combined to issue a pivotal and far-reaching report in 1921 (see Correlation).

The Relief Society experienced these same trends. Its first three twentieth-century presidents, Zina D. H. Young (1888-1901), Bathsheba W. Smith (1901-1910), and Emmeline B. wells (1910-1921), all remembered the Nauvoo organization. For them women's meetings were to be spontaneous, spiritually active, and locally determined. The new century, however, redefined their vision. In 1901 a few lesson outlines were provisionally provided. Twelve years later, with the recommendation of a Church correlation committee, Relief Society leaders adopted a uniform, prescribed curriculum. They also implemented uniform meeting days (Tuesday), record books, and a monthly message for the visiting teaching women who made monthly home visits. In 1915 an official Relief Society magazine replaced the semi-independent woman's exponent, a voice for Relief Society since 1872. While the First Presidency at first endorsed the continuation of female prayer healing—often undertaken in meetings on an impromptu basis—the practice dwindled and by mid-century was abolished. As a further sign of centralization under priesthood leadership, the Relief Society was housed in the Bishop's Building and increasingly received its direction from the Presiding Bishopric rather than the First Presidency. Though Relief Society had once played a role in developing and supervising the Primary and YWMIA, their supervision of the children's and youth auxiliaries ended.

The Relief Society's later presidents, Clarissa S. williams (1921-1928), Louise Y. robison (1928-1939), and Amy Brown lyman (1940-1945), cooperated in these changes. Speaking for modernism and efficiency, they and their advisory boards set aside such past tasks as home industry, silk culture, and commission retailing in favor of community outreach; "scientific" or professionally trained social work; campaigns against alcohol, tobacco, and delinquency; and, during the Great Depression, public relief. The latter effort was crucial. "To the extent that Relief Society Organizations in Wards are operating in cooperation with Priesthood Quorums and Bishoprics," declared Elder Harold B. Lee, who led the Church's relief efforts, "just to that extent is there a security [welfare] program in that ward" (Relief Society Magazine 24 [Mar. 1937]:143). These efforts reflected the early-twentieth-century Mormon feminine ideal. Women were to uplift, soften, and assist. While women leaders continued to play an active role in the National and International Council of Women, the rank and file were less active in political, social, and professional roles than in homemaking.

Several doctrinal issues were clarified, another indication of systematization at work. From the early years of the Snow administration, Church authorities discussed how strictly the 1833 health revelation, the Word of Wisdom, should be obeyed. In 1921 the question was answered by making abstinence from alcohol, tobacco, tea, and coffee one of the standards for admission to temples. During the century's first three decades, the health code led most Latter-day Saints to support local, state, and national prohibition.

In 1909 the First Presidency issued a statement designed to clarify the Church position on evolution. While the method of creation was not discussed, the declaration held that "Adam was the first man and that he was created in the image of God." The issue remained troublesome, however. Along with the question of higher biblical criticism, it led to the resignation of three Brigham Young University professors in 1911 and to extended private discussion among Church leaders two decades later.

In 1916 the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve issued a second important doctrinal exposition entitled "The Father and the Son." Apparently occasioned by anti-Mormon pamphleteering charging the Church leaders with conferring divinity on Adam, the statement delineated the respective roles of the first two members of the Godhead. Shortly before his death, Joseph F. Smith received a vision of missionary work and spiritual existence in the afterlife, which was eventually included as Section 138 in the Doctrine and Covenants. In addition to specific matters, general LDS doctrine and history received systematic treatment, often for the first time, by such works as President Smith's Gospel Doctrine, Elder James E. Talmage's Articles of Faith and Jesus the Christ, and Elder B. H. Roberts's three-volume New Witnesses for God.

With its membership still predominantly American, the Church was especially affected by the events occurring in the United States during this period. Almost from the outset, President Grant's administration was beset with hard times. Farming and mining, two of Utah's main industries, slumped badly in the 1920s and especially in the 1930s during the Great Depression. President Grant carefully conserved Church finances, trimming expenditures and construction projects. Using his contacts with national business and political leaders, he kept key Utah and Church-owned enterprises afloat. He was also concerned for the individual Saint. After careful preparation, he announced in 1936 the Church Welfare Program (see Welfare Services), which sought self-sufficiency and sustenance for the needy by simultaneously providing both work and needed commodities.

Despite difficult times, the Church maintained its primary functions. Just prior to the economic downturn, it completed an imposing five-story building in Salt Lake City. Temples were completed in Hawaii (1919); Cardston, Alberta, Canada (1923); and Mesa, Arizona (1927). Education also received attention. Between 1875 and 1911, the Church established thirty-four all-purpose academies. However, as the century progressed, financial distress and the rising acceptance of public education brought changes, and many of the academies were closed or transferred to state control (see also Education). The Church, however, did not entirely surrender its educative role. A released-time seminary program for high school students began in 1912 (see Seminaries), and during the 1920s, institutes of religion for college students were established, the first at the University of Idaho.

Twentieth-century wars and warfare demonstrated the distance the Church had traveled from nineteenth-century alienation and isolation. Latter-day Saints supported the Spanish-American War effort and U.S. involvement in the two twentieth-century world wars. In the former the First Presidency issued a statement affirming the loyalty of the Latter-day Saints and telegraphed local leaders to encourage enlistment. Utah became one of the first states to fill its initial quota. Involvement in World War I was even more substantial. At first uncertain of its proper role, the Church eventually helped Utahans oversubscribe the government's financial quota for the state. By September 1918 Utah had more than 18,000 men under arms, almost half of them volunteers. Participation in the Second World War was more dutiful, perhaps because of the private misgivings of President Grant and his Counselor J. Reuben Clark over New Deal policymaking. Nevertheless, by April 1942, 6 percent of the total Church population served in the American forces or in defense-related industries; others served for Canada, Britain, and Germany.

While each conflict saw some pacifist currents and even opposition, the general tendency was supportive of the need to yield loyalty to constituted government. "The Church is and must be against war," the First Presidency declared in April 1942. Yet when "constitutional law…calls the manhood of the Church into the armed service of any country to which they owe allegiance, their highest civic duty requires that they heed that call" (CR, pp. 88-97; see War and Peace).

While documenting religiosity is difficult, statistics suggest the impact of the Church on the everyday life of its people. Meeting attendance showed sturdy growth throughout the era. In 1920 weekly average attendance at Sacrament meeting was 16 percent; in 1930, 19 percent; in 1940, 23 percent; and 1950, 25 percent. Suggestive of Church family ideals, LDS birthrates exceeded the national average, as did marriage rates. No doubt the Church health code is reflected in the fact that in 1945 the LDS death rate was about half the national average.

A closer view of statistics reveals that in the decades of the early twentieth century the number of children born per LDS family declined, the age at time of marriage increased, and divorce ratios often mirrored national trends—lingering behind but moving in the same direction as national trends, as if assimilation were simply incomplete (see Vital Statistics).

The half-century brought social, cultural, and political integration; growth and consolidation; and programs that redefined and reapplied earlier Church ideals. But the era also produced indications that Church members were not immune to such broad currents as secularism and even materialism. For observers, at mid-century basic questions remained: Could the Church preserve its traditional values and energy? Or would its journey into the modern world cost the movement its identity and mission?

(See Daily Living home page; Church History home page; 1898-1845 home page)

Illustrations

In 1898 the Church found itself saddled with large debts earlier incurred to finance water and irrigation projects, sugar beet and salt factories, power plants, railroads and the completion of the Salt Lake Temple. Lorenzo Snow became president of the Church on September 13, 1898, and took immediate steps to remove this financial burden. He emphasized payment of tithing and on December 1, 1898, issued these eleven-year six-percent bonds. Half of the bonds were redeemed within five years and the entire debt was retired in 1907.

The laying of the cornerstone of the Church Offices (now called the Church Administration Building) at 47 East South Temple, Salt Lake City. The building was completed in 1917. Photographer: Albert Wikes. Courtesy the Utah State Historical Society.

The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (1941-1943) on the steps of the Church Administration Building. Right to left: Rudger Clawson, [George Albert Smith—not present], George F. Richards, Joseph Fielding Smith, Stephen L. Richards, Richard R. Lyman, John A. Widtsoe, Joseph F. Merrill, Charles A. Callis, Albert E. Bowen, Sylvester Q. Cannon, Harold B. Lee.

Bibliography

For general surveys of the period:

Alexander, Thomas G. Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890-1930. Urbana, Ill., 1986.

Allen, James B., and Glen M. Leonard. The Story of the Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, 1976.

Arrington, Leonard J., and Davis Bitton. The Mormon Experience. New York, 1979.

Church Education System. Church History in the Fulness of Times. Salt Lake City, 1989.

Cowan, Richard O. The Church in the Twentieth Century. Salt Lake City, 1985.

Roberts, B. H. A Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, 1930.

For LDS programs, policies, and teachings during the period:

Alexander, Thomas G. "Between Revivalism and the Social Gospel: The Latter-day Saints Social Advisory Committee, 1916-1922." BYU Studies 23 (Winter 1983):19-39.

Alexander, Thomas G. "The Reconstruction of Mormon Doctrine: From Joseph Smith to Progressive Theology." Sunstone 5 (July-Aug. 1980):24-33.

Alexander, Thomas G. "To Maintain Harmony': Adjusting to External and Internal Stress, 1890-1930." Dialogue 15 (Winter 1982):44-58.

Hartley, William G. "The Priesthood Reform Movement, 1908-1922." BYU Studies 13 (Winter 1973):137-56.

Hefner, Loretta L. "This Decade Was Different: Relief Society's Social Services Department, 1919-1929." Dialogue 15 (Autumn 1982):64-73.

Encyclopedia of Mormonism, Vol. 2, History of the Church

Copyright © 1992 by Macmillan Publishing Company

All About Mormons |